Guest article

Light strategies, heavy changes

Architect and urban designer Sol Camacho—founder and director of RADDAR, a firm out of São Paulo and Mexico City—on architecture as a tool for change.

Written by: Sol Camacho

Oct 29, 2024

6 minutes

During a week-long seminar at São Paulo’s Escola da Cidade Architecture School, my colleagues Gabriela Carrillo, Aisha Ballesteros, Loreta Castro, and I prompted our students to think about architecture as a tool for change and a lens through which they should critically view the world.

The conversation centered on the importance of accessible cultural and community places. Mexico City and São Paulo, both cities that I call home, contain mostly segregated private buildings that are largely unable to hold, help, and foster safe and gentle human relationships. During the seminar, we examined projects that center on repair, retrofit, and reuse that offer an alternative approach.

First, we asked the students some paradoxical questions:

How to densify spaces without over-programming?

Can we use technology to foster unplugged human encounters?

Can light structures have a heavy impact on spaces?

Can temporary infrastructure have a permanent result in our cities?

Can we build new places without constructing more buildings?

Reflecting on the seminar, I’ve been thinking of how the work of my co-instructors, as well as my own practice, embodies what we shared with the students.

Projects that repair and transform

“In our broken built environment, we’re all working retroactively,” says Loreta Castro. Her Taller Capital repairing projects demonstrate how design can be generous, and when applied rigorously, transformative. This goes for all scales, from large public parks, like Parque Bicentenario in Ecatepec, Mexico City, to building interiors, like the reconstruction of the Iguala Municipal Building—which offers direct public access to its gardens and auditorium.

Light structures, or delicate gestures, can definitively have a heavy impact in our collective spaces. By delicate, I mean strategic, intelligent, and efficient. In this sense, our seminar turned to Lina Bo Bardi’s SESC Pompeia. She envisioned the transformation of an old oil tank factory into a community center. With demolition-free construction, featuring simple walls and inventive furniture design, SESC Pompeia has thrived as a community center for decades.

Obsolete or underused large structures hold some of the most interesting creative possibilities for designers.

Sol Camacho, Architect

Aisha Ballesteros’ recent transformation of an ice factory into an office workshop for her firm JSa Arquitectos takes inspiration from the revolutionary Lina SESC project. In need of larger space, JSa Arquitectos settled in the industrial area of Atlampa. Although only a few kilometers away from historical downtown Mexico City, the neighborhood has historically been underserved. The Fabrica de Hielo project not only gives the firm a new workplace, but also positions itself as a place to meet, a learning space, and a social center open to the local community. All of this was achieved without adding to the footprint.

Giving buildings a second life

Obsolete or underused large structures hold some of the most interesting creative possibilities for designers. My office, RADDAR (which stands for Research as Design and Design as Research as Design—the foundational principle of our practice) has had the opportunity to work with such buildings near central São Paulo, including small-scale retail spaces.

Part of the ground floor of COPAN, Oscar Niemeyer’s signature urban structure, was abandoned for more than 20 years after serving as a bank agency in the 1970s. Our work was to renovate this northernmost part of the floor, including a 30-meter facade and rethink the interior into a contemporary restaurant. We organized the restaurant around the structure’s gorgeous column design and created furniture designed specifically for it. Since its renovation, the area has become a staple place of the daily urban São Paulo cultural scene.

Design does not exist in isolation, and collaboration is the key to driving ideas.

Sol Camacho, Architect

The Itu House project, a derelict storage building that was transformed into a vibrant mixed-use space, is also the result of the belief that light strategies result in heavy changes. The building, which had been abandoned for more than a decade and was on the cusp of demolition, is now a hybrid structure that questions the norms around what a house in São Paulo should be. The project blurs, in a contemporary way, the ideas of public and private spaces and creates new understandings around community and family.

Restoring a beloved gem for the community

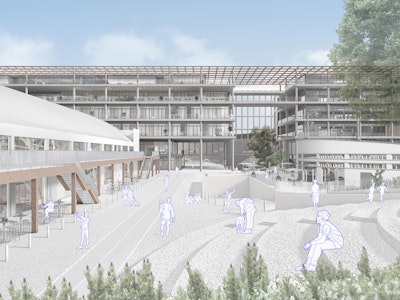

In a similar spirit, our Pacaembu Project questions the stadium typology in our contemporary city. The Pacaembu Sports Complex was originally built in São Paulo in the late 1930s in as the first large-scale soccer stadium in Brazil, as well as a space for civic and cultural activities. As soccer evolved into a mass-media event, stadium sizes had to keep pace. As a result, Pacaembu was relegated as a secondary stadium, and its cultural and civic facilities were demolished or left underutilized.

The huge urban infrastructure sat in the middle of the city void of its potential, marked by demolitions, lack of maintenance, and severe degradation. But fan sentiment and the community’s fond collective memories left Pacaembu hanging on by a thin thread.

For the past five years, we have worked on the renovation, which is now in an advanced stage of construction. With this project, structured as a public and private partnership, we reimagined the stadium as an everyday meeting place. The result introduces spaces for the community to gather, with a public Olympic-sized swimming pool, tennis courts, basketball and volleyball gyms, a running track, a jogging trail, leisure amenities, restaurants, and places to pop in and work. Throughout the year, the building will house events, from large concerts to small recitals.

The result of this large-scale intervention will give birth to a one-of-a-kind typology: a multi-use urban center with a professional soccer field at its center.

Looking to the future with a fresh approach

Design does not exist in isolation, and collaboration is the key to driving ideas. As designers, architects, and built-environment professionals, we ought to look for places and opportunities to let communities thrive, and keep that notion at the core of our decisions. Through repair, retrofit, and reuse, we can change the way we approach architecture, leading to a ripple effect that can change the lives of the people that interact with our projects.

About the author

Sol Camacho is an architect and urban designer who founded and directs RADDAR, an architecture firm based in São Paulo and Mexico City. Camacho also served as the Cultural Director of the Instituto Bardi/Casa de Vidro Institution. Camacho holds a B.Arch from Universidad Iberoamericana and a Masters in Architecture and Urban Design from Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Additional image credits

First image:

Aerial view of the Parque Bicentenario in Ecatepec. Courtesy Taller Capital. Photographer: Rafael Gamo.

Second image:

Interior of the JSa office (old ice factory). Courtesy JSa. Photographer: Rafael Gamo.

Newsletter

Our newsletter serves up insights, design ideas, project profiles, and more Design with Impact content—right in your inbox.

Hungry for more?

Explore more ways we can help you expand your impact on your organization and the world.